Somos Martina is a Colombian brand redefining menstruation with absorbent underwear for bodies.

Subscribe to our newsletter for updates.

Menstruation in Colombia: Inequality Starts in School

Written by

Maria Fernanda Fitzgerald

Biological

“I remember we had just finished performing a school play,” says Dulce. Her voice, as gentle as her name, softens as she recalls the first time she got her period at school. She was in ninth grade back then, now she’s in tenth, but that day remains etched in her memory.

“When I took off my costume after the play, it was completely stained.

“That day I was called and had to bring her a full change of clothes, because the school didn’t have anything available for her,” recalls Katherine, Dulce’s mother. She also remembers how, in order for her daughter to remain in school that day, the school required her to wear the official uniform: They wouldn’t let her attend class

Every month, Dulce’s period feels like a test.

For Mariana, a 15 years old teenager from the outskirts of Bogotá, the experience feels familiar: “At our school we have to justify to our teachers why we’re going to the bathroom. Sometimes I feel too ashamed,

”Girls and women across Colombia face the same problem every month: having their period becomes an obstacle. For school-age girls this reality is particularly harsh. It leads to absenteeism, which in turn increases the risk of dropping out, widening the gender gap

According to DANE, one in seven women in Colombia experiences menstrual poverty,

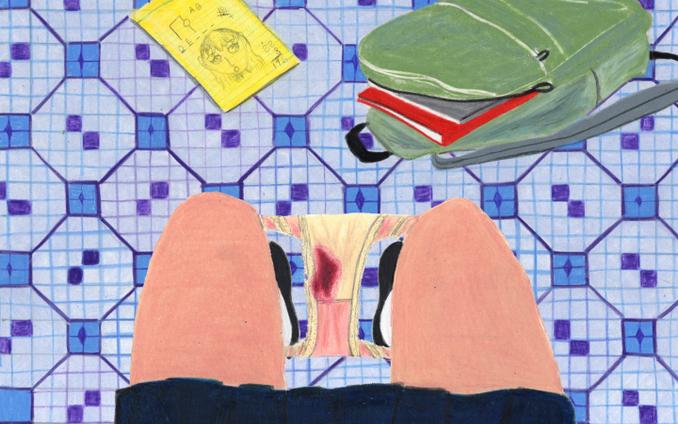

A small trail of blood runs down a thigh. Photo: Violeta Zambrano

Left Alone

Menstrual cramps are far more than a discomfort: for many teenage girls, they are a barrier to attending school.

“Many teachers don’t even let us go to the bathroom. If I go to the nurse’s office to ask for a simple herbal tea to deal with the pain, they tell me they don’t have any. That’s why I often prefer to stay home,

A study by Fundación PLAN in schools in Colombia’s Pacific region collected testimonies from girls describing how pain forced them to leave school early or remain in class unable to focus. The study documented a clear pattern: apart from the pain, the cramps become a silent form of exclusion. Girls are physically present but mentally absent, disconnected from lessons, paralyzed by pain, and lacking support

The Cost

The lack of adequate menstrual products is a severe problem.

This difficulty is even more acute in lower-income households. A study cited by Infobae reports that more than 90% of women from Colombia’s lowest socioeconomic strata lack access to basic menstrual hygiene products.

“This shows that when menstruation occurs in contexts of socioeconomic vulnerability,

Absence due to Menstruation

- 52%

- Of girls in Colombia have missed school due to menstruation.

(Buitrago, 2024)

Affordability of Menstrual Products

- 15%

- Of girls and women in Colombia who menstruate cannot afford period products.

(DANE, 2022)

“At Dulce’s school, we once tried to raise some extra funds to install a machine that dispensed sanitary pads,” recalls Dulce’s mother, “but when we began to implement it, the school refused to continue, saying it was unnecessary and that the money would be better spent

In Colombia, 32% of the population survive on just 25 USD per week or less (DANE), while access to menstrual products remains both limited and costly.

While reusable menstrual cups are more affordable than single-use products, they are not intuitive, invasive, and require privacy and frequent maintenance — which can be a challenge for students. Reusable pads, though simpler to use, can shift out of place and need regular washing and drying, which isn’t always practical in a school setting. Menstrual underwear, while slightly more expensive upfront, is easier to use, more comfortable,

Without menstrual products, girls in Colombian schools feel exposed and constantly worried about stains;

No Infrastructure, No Dignity

Many schools and other public spaces in Colombia lack

“At my school, I can’t find some of the basic things I need when I get my period. I usually try to use pads, even though they often irritate me. I have to, because when I tried using a menstrual cup, I realized there were no individual bathrooms (only shared ones) so I had nowhere to wash

UNICEF data shows that in rural and remote areas, more than one in four girls have missed school at least once due to not being able to manage their periods at school. Additionally, DANE reports that over 300,000 women in Colombia lack access to private bathrooms, clean water, or basic hygiene items.

Despite a government initiative to a school sanitation facilities, there is still a long way to go

Silence Turns Into Stigma

The silence surrounding menstruation weighs heavily. In Colombia, the lack of open and honest conversation on the subject is tied to the fact that many girls aren’t properly educated about their bodies.

According to Fundación PLAN, 90% of girls in vulnerable communities lack basic knowledge

Beyond economic hardship, studies show that many girls experience shame or ignorance at their first period. In rural or remote areas, a UNICEF survey found that one in three girls did not know what menstruation was before experiencing it for the first time.

Awareness of Menstruation

- 34.8%

- Of Colombian girls didn’t know about menstruation before their first period.

(UNFPA/UNICEF, 2016)

Stigma Around Menstruation

- 30%

- Of Colombian girls feel ashamed to talk about menstruation.

(Fundación Plan, 2019)

This lack of knowledge is compounded by Colombia’s deep-rooted conservative-Catholic attitudes toward women, sexuality, and the body. In many communities, discussions about menstrual cycles are considered inappropriate or overly private, linked to ideals of modesty and purity that limit openness. These cultural codes rooted in religious teachings and patriarchal norms—reinforce the taboo:

This silence and absence of education generate stigma,

“I’ve never felt comfortable enough to ask a teacher for help during my period,” says Dulce. “I’d rather turn to my classmates, but I only do it if I have no other option.

From Isolation

The stigma surrounding menstruation can motivate teasing or ridicule from classmates, which further damages girls’ emotional well-being. In Colombia, 23% of female students reported being victims of bullying

Missing several classes has a cumulative effect: difficulty keeping up with lessons, falling grades, widening gaps with peers or even dropping out

Child-Marriages Based on Education

- 61%

- Of Colombian women with only primary education were married as minors. ,

- 20%

- Of Colombian women with secondary education were married as minors.

(UNICEF, 2023)

Income Based on Education

- 3.3k COP

- Average hourly wage for Colombian women with only primary education. ,

- 4.5k COP

- Average hourly wage for Colombian women with secondary education.

(DANE, 2022)

Inequality That Lasts a Lifetime

Menstruating in adverse conditions becomes yet another

In Colombia, economic inequality

From Conversation to Policy

A first step to improve the situation would be to recognize menstrual education as a right.

Infrastructure is also crucial: schools with properly equipped private bathrooms make the difference between attending class and staying home. But these changes will not be enough without policies that guarantee universal access

For Dulce, it all comes down to willpower: